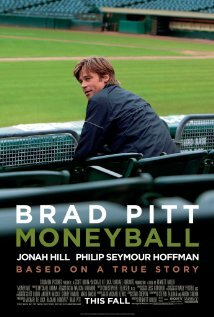

Bennett Miller’s Moneyball is not like most other sports movies. In most sports movies, no matter which game they concern, the drama takes place in the arena – on the basketball court and the football field, in the boxing ring and the baseball diamond. It is there that muscular athletes conquer pain, adversity and inevitably sharp odds to steal victory (or occasionally suffer honourable defeats) in front of lights, cameras, disbelieving commentators and the caterwauling of the crowd. Not so in Moneyball. Based on the non-fiction book by Michael Lewis, and with a script by Academy Award winners Steve Zaillian (Schindler’s List) and Aaron Sorkin (The Social Network), Moneyball sets its drama not just in stadiums, but also in offices and in boardrooms. While its compatriots focus on strength, Moneyball celebrates strategy, recounting the unlikely true story of how brains triumphed over brawn, and mathematics changed America’s favourite past-time forever.

In 2001, the Oakland Athletics baseball team were knocked out of the American League series finals by the New York Yankees, a side with nearly four times the A’s budget. With the next season just around the corner, the A’s general manager Billy Beane (Brad Pitt; Inglourious Basterds) is left in charge of fielding a competitive team with a less than adequate funds, while also faced with the departure of three of his star players for more profitable pastures, and a coach (Phillip Seymour Hoffman; Miller’s Capote) understandably concerned about the single year remaining on his contract. Driven to desperation, Beane hires Peter Brand (Jonah Hill; Get Him To The Greek), a fresh-faced Yale economics graduate who has devised a radical method of team selection using statistics – called sabermetrics – that flies in the face of the conventional wisdom of the scouts.

Billy Beane is a great part for the maturing Pitt, whose recent work in films like The Tree of Life and The Curious Case of Benjamin Button has seen him gracefully transition from his boyish Hollywood persona to something closer to a quintessentially American man. In Moneyball, Pitt captures without unnecessary flair all the frustrations of a man for whom victory has always been elusive. Across from the A-lister, Jonah Hill gives the first real dramatic performance of his admittedly short career, holding his own against the rest of the cast and demonstrating the same inner determination that his nervous character does when his statistical wizardry faces opposition from his colleagues.

Sadly, Phillip Seymour Hoffman, who scored well deserved Oscar gold in his last outing with Miller, is largely wasted. In his role as the aging team coach, Hoffman represents the old guard of the Oakland staff; the dinosaur who refuses to evolve. As such, he is offered the significantly reduced screen-time that befits a creature on the verge of extinction. This is indicative of the film’s most niggling flaw: Miller, Sorkin and Zaillian simplistically chalk up the early failings of the sabermetric approach to a bull-headed old man who refuses to play the team as intended. However factually accurate this may be, the films depiction of the young versus the old – of the clashes between Beane and his aged staff – feels thin, unkind and often unconvincing.

Where Moneyball really takes off is when Brand and Beane’s gamble starts to show dividends. Scenes of rapid fire dialogue, such as when the two traders juggle half a dozen phone calls and counteroffers to secure a new player and screw over a rival team, are far and away the best parts of the film, recalling the frantic energy of the stock exchange (although not quite in the same ballpark as Sorkin’s Oscar winner from last year). The excitement is then ratcheted up on the pitch as well, as the A’s edge ever closer to twenty victories in a row and a place in the American League record books. Under the artificial stadium lights, Miller and cinematographer Wally Pfister (Inception) shoot the matches with icy elegance. But inevitably they return to the offices and corridors with Beane, whose mind keep ticking – and whose phone keeps ringing – long after the fans have gone home.

With the film running a tad over two hours, Miller might have been a little tighter with his editing. Sugary scenes between Beane and his precocious daughter could have easily been removed, as could some of the many shots of the man driving around in his truck looking introspective. These moments, meant to humanize a character who doesn’t need to be likable, ring false. It’s enough that we know that Beane is a former baseball prospect himself, and that victory with the A’s would make up for all those years of disappointment. Beane has honour and loyalty. But he is also a cynical man, capable of firing players like they’re nothing more than scribblings on a whiteboard. Brand and the rag-tag Oakland team are there to be liked, but Beane is there to count the pennies. Moneyball is at its best when it’s all about the numbers.

Follow the author Tom Clift on Twitter.

Follow the author Tom Clift on Twitter.