Quirky is the new cool. Introverted is the new extroverted. Freeze frames are the new flashbacks. And if that montage doesn’t come with a wry voiceover or a dry folk-rock track, you might as well forget about it.

These are a few of the unwritten laws of the coming-of-age indie: films that are so concerned with being different, they’re at risk of becoming the same. Sometimes, the quirkiness comes across naturally and with artistic merit, such as in Spike Jonze’s Where the Wild Things Are. Often, however, it comes across as self-satisfied and artificial, such as in most movies starring Zooey Deschanel.

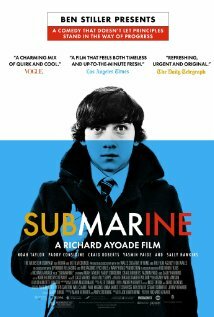

Richard Ayoade’s Submarine sits somewhere in-between. It’s too concerned with style to leave a lasting impression, yet it’s also warming and witty enough to pass by without doing any harm. I’ve seen this movie before. You have too. Perhaps if it didn’t pretentiously presume otherwise, it might have been something more than moderately charming.

Adapted from the 2008 novel by Joe Dunthorne, Submarine tells the unique-yet-universal tale of angsty Welsh teen Oliver Tate (newcomer Craig Roberts). Oliver imagines his life is a movie (it is). Oliver reads the dictionary for fun (it isn’t). Oliver would very much like to lose his virginity to the “moderately unpopular” Jordana (Yasmin Paige), whose fiery nature – she enjoys the odd bit of arson – is something he both fears and admires. At home, Oliver is worried that his parents (Noah Taylor and Sally Hawkins) are on the verge of separating, especially since they haven’t had sex in seven months. He knows this because he checks the light dimmer in their bedroom each morning. And it hasn’t been dimmed in a while.

If it wasn’t for Craig Roberts’ amiable performance, Oliver’s forced foibles and general air of conceit might have been hard to swallow. Yet he wisely understates instead of overstates, successfully counterbalancing the exaggerated editing and sound design that threatens to define the film. More laudable, however, is Noah Taylor and Sally Hawkins as Oliver’s detached, depressive parents. They use silence to convey more than Roberts’ incessant narration ever could.

In his first feature, Ayoade’s handling of the material is confident and considered, even if he wears his influences – such as Wes Anderson and Francious Truffot — on his sleeve. Despite its obviousness, the initial onslaught of indie eccentricity does produce some solid laughs, particularly Oliver’s daydream depiction of his own funeral. Still, I was glad to see it take a backseat during the second half where the film stumbles upon a beating heart.

So was I moved? Not particularly. Everyone in Submarine is so deadpan, it seems only fitting that we respond in kind. But that’s not to say I wasn’t unmoved, either, as there’s a lot of truth spoken here. I suppose I was satisfied. Satisfied by what is a well-meaning and, for the most part, well-made film. Satisfied in the knowledge that the best of everyone involved – especially Ayoade — is yet to come.

Follow the author Anders Wotzke on Twitter.

Follow the author Anders Wotzke on Twitter.

![Submarine_RobertsTaylor[1] submarine robertstaylor1 600x400 Submarine (Review)](/wp-content/uploads/submarine_robertstaylor1-600x400.jpg)