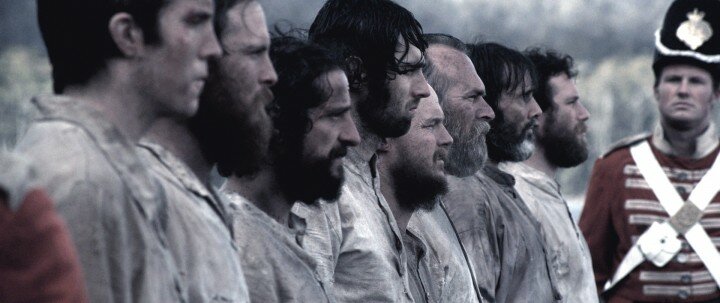

Van Diemen’s Land has already enjoyed sell-out screenings at festivals across Australia (including the world premiere at Adelaide’s own Bigpond Adelaide Film Festival) and selection at Edinburgh and Montreal. On its impending Australian general release we talked to director Jonathan auf der Heide and star Oscar Redding, who revealed their thoughts on the dark side of human nature, slow evolution and a womanising convict.

CUT PRINT REVIEW: You were both executive producers and writers on the film… what did you find compelling about the story and what did you want to tell?

Oscar: (to Jonathan) Ah, you want me to take this one? Well, there were a few things… I think it’s just a ripping yarn, when I first heard it my jaw dropped and I thought it was just an extraordinary story. You could probably intellectualise it out to be something like the human spirit at its most extreme and human behaviour also at it’s most extreme, so it’s kind of something that by having a look at those things and investigating what that is, you might get an inkling of the absolute possibility of what it is to be alive. It’s kind of interesting but as I say, a great bloody story and every person I’ve told it to has firstly said it’s a ripper story and secondly that’s got to be made into a film so that was probably a good idea.

Jonathan, you’re from Tasmania: this is a darker period of the state’s history – why did you want to point out the dark side of your home?

Jonathan: I think that Tasmania’s more guilty than anywhere else, you know, sweeping the convict stain under the carpet, hence it’s changing the state’s name from Van Diemen’s Land to Tasmania. Which is a pretty bold move, to change the name of the state so that we wouldn’t be recognised as having a convict heritage, because for them Van Diemen’s Land was a dirty word; it meant that it was a colony full of thieves and lowlifes, but I think it’s really important to open up that door and drag the skeleton out of the closet because we have to look where we come from to know where we’re going and so I think it’s just a fascinating neglected chapter, especially in film. There hasn’t been a convict film since 1927, For the Term of His Natural Life was the last one… so as a Tasmanian I think it’s quite important to look at our stories whether they’re dark or not. I mean, there are a bunch of fascinating stories of our history that haven’t made it to film, whether they’re happy or not… There’s definitely an audience out there now who as soon as they hear the title Van Diemen’s Land they’re just biting at the bits for some sort of convict film to be made. There’s room for it you know, it’s the first one since 1927!

|

|

Why do you think a convict film hasn’t been made for so long?

Jonathan: I think that it began with that convict name thing where they didn’t want to celebrate or embrace the darker aspects of our past, and just wanted to congratulate and acknowledge all the achievements we’ve done and not so much the less prouder moments. It wasn’t until the 1970s that people really started to look at our convict history and go ‘oh wow, there’s really fascinating stuff’. It’s a reaction to that, but it’s just taken a while for film to catch up with what literature’s been doing for thirty years.

There’s a lot of philosophical stuff about our predatory nature with quotes like “a man with blood on his hands is no man.” What would you say about human instinct?

Oscar: For us when we got into the story and we were writing it, there was something about the dare of taking the audience on this journey, as I was saying before, on the ability of extreme human behaviour and perhaps the possibility of that existing in every one of us. It certainly feels like that to me, having gone on this journey with the film where this Pearce character didn’t seem to begin differently from any of us who would perhaps be thrown into whatever those circumstances were, so we were aware of the difficulty of people just following along with a smile on their faces so it’s always a thing of giving people this material and these quotes which seem to indicate where Pearce was in his head but also to invite people to explore what this stuff is – which seems kind of essential in what it is to be human. I think by not thinking about stuff which is a little bit more difficult to deal with in our own behaviour it doesn’t help us with our everyday life if we don’t have some kind of critical ability to deal with this stuff.

Jonathan: Pearce has been portrayed as a monster in the past which is a much easier thing to do, to pigeonhole him as a psychopath, but what we wanted to do was humanise him and make the audience relate to this man and see him as someone no different to you or I.

Pearce’s presence is progressive throughout the film although he remains the crux of the story. Was that a conscious decision in the writing process for his prevalence to come out later on?

Jonathan: We had already seen Pearce as the everyman of the group; he wasn’t the leader or the obvious choice of who would survive. It could’ve easily been The Robert Greenhill Story, because he was the navigator. It’s just a matter of the battle of wits and who managed to come out on top and I think we were quite interested in Pearce just being the everyday member of the group who could be any one of us and not to highlight him so much as a hero or an anti-hero so much but just as someone who’s quite the observer, who can manipulate the group in a way and not draw attention to himself amongst the group, and it’s through that he managed to survive until the very end.

Van Diemen’s Land is essentially about the ‘last man standing’. Why do you think audiences like watching these types of stories?

Jonathan: We’ve always been drawn to stories of human survival and of going to extreme lengths in order to survive and it’s just in our nature to celebrate these stories because we as human beings, since the dawn of time, have had to endure these types of stories and it is something that’s missing from our everyday lives now because everything’s served to us on a platter. Sure, we work really hard, do the day jobs and go to the supermarket and get our food, but there is something fascinating about being put to the extreme to test our endurance and I think people like being put in those shoes for a couple of hours.

|

|

Oscar: It’s almost like the same reason you watch sports, you don’t know what’s going to happen in the end; it’s kind of existent on that level as well.

Jonathan: People love books or films like Lord of the Flies, Apocalypse Now or Deliverance; these sorts of stories where it is very much about men exploring the depths of human nature and how far they will go in order to survive and the battle versus nature and how we overcome it. We always want these stories.

Do you think within Australian film we have many stories that are as strong as Van Diemen’s Land in terms of our past history?

Jonathan: We have heaps of stories like this – watching The Proposition the other year was quite exciting for me and a lot of people; we did approach these stories thinking they were as interesting and cool as any American western, and there’s no reason why we can’t tell them. I’m hoping that after Van Diemen’s Land we’ll open the door and tackle these stories in quite a brutal and uncompromising way… there’s plenty of room for more stories like this one.

Is there any particular story either of you would like to tackle?

Jonathan: We flirted with the idea of the Matthew Brady story, which is another escape from Macquarie Harbour – so we obviously don’t want to do that next! He was the ladies’ man bushranger from Macquarie and was going to start an uprising there, but then became a bushranger in Hobartown and he was too busy flirting with all the ladies that he never made it back! He was quite a character, and when he was hanged apparently there was a huge turnout of women throwing their underwear and flowers at him.

You could make that into a satire…

Jonathan: (laughs) Yeah!

Back to Van Diemen’s Land: Oscar, the shoot looks like it would’ve been gruelling – how did you prepare for the role of Pearce?

Oscar: Quite a bit. I was aware about the conditions and that we were going to be shooting in winter at the height of the rainy season down in Tassie, and we wanted as much rain as we could get. I was having cold showers just so I could adjust my body to the cold temperatures we were going into, doing that stuff to make sure when we got on set that I didn’t drop dead because of the freezing cold. It certainly seemed to help; I was a bit more adjusted. We had Mark Leonard Winter and Tom Rice in the film who’d just come off Balibo, so they’d walked off a set which was 40 degrees onto ours and I felt pretty sorry for those guys. We were hosing down in the middle of the night and getting them to do a cold fire scene.

Jonathan: Well, Oscar also learnt Irish-Gaelic in preparation for the film. He doesn’t like to brag about that one! But he did piss off to Ireland for a few months and worked towards translating the film because most of the film’s dialogue is in Gaelic because it’s Pearce’s native tongue.

You wanted to keep authenticity by using it then?

Jonathan: Yeah, well, our only way into the story of Alexander Pearce is through his confessions, so he is our avenue into this story. We wanted to follow him but as we said before we didn’t really see him as the charismatic leader of the group, so the only way we could access what was going on in his mind is through the Irish voiceover. It was to be authentic to that, but also to remind people that these guys were from another land and their first language may not have been English so as soon as an Australian sees the Tasmanian rainforest which is quite a beautiful thing, we’ve probably seen pictures of it before. Then if there’s an Irish voice with subtitles on the image we’re alienated from that, and realise how these guys had never actually seen terrain like this before… how would they react to that?

Australia is so multicultural now but the film shows diversity back then, doesn’t it?

Both: Yes.

Jonathan: We’ve had a lot of immigrants who have come to this country who have related to this film quite strongly because that’s what Australia is; from the very beginning it was a melting pot of cultures. You had the English, Irish and Scottish people coming to these shores where it is completely foreign and alien to them. They don’t understand the landscape, and they have to adapt in some way and it does toughen them up as people, and I think the immigrants today have to do a similar thing – that gives us a sense of an Australian identity.

Warning: The hidden section below consists of spoilers. Reveal the section by clicking the spoiler button.

|

|

[spoiler]Oscar, what do you think gave Alexander the strength to survive over the others?

Oscar: A couple of things; he was probably just lucky in some way but I think, certainly for us telling the story, he seemed to be willing to do things that no-one else would be willing to do and I think that possibly is the question mark over his strength as a person in some way. I don’t want to give the story away but when he allows for his friend to be killed… from that moment on he becomes the most dangerous person there simply because he’s willing to do something no-one else in the group would do.

He’s almost dehumanised by it isn’t he?

Oscar: Yes, it’s an extraordinarily big shift for him – it’s not meant to be mapped out or cemented so that everyone goes ‘oh well, he’s becoming a different person’, but that is probably the cause and effect of the rest of his journey; that moment where he decides to do something and he’s probably aware of the fact that it’s something which no-one else there could do. That’s obviously a part of our storytelling and our writing and whether he was liked or not is complete conjecture, but there must’ve been something in this man that besides from his luck was a strength, tenacity and determination which is in most people that I’ve met in this country. We (Australians) have Booker Prizes, science prizes, Academy Awards, gold medals and all that sort of stuff and a population of 21 million people which is ridiculous. [/spoiler]

Jonathan, what was the decision behind not showing much of the settlement itself in the film? Did your work on Hell’s Gates (a ‘prequel’ of sorts) influence that?

Jonathan: No… We do show the settlement they escaped from in the first scene but I didn’t want to focus so much on the brutality of the place they were escaping. I do hint towards it during the film, about receiving lashes and all that but I really wanted to avoid the cliché of convicts and chain gangs and that kind of crap. The story isn’t about that. What Oscar and I have spoken about quite a lot has been that approach of nature versus nurture, whether Pearce is simply a product of colonial Australia or whether he as a human being has this heart of darkness that he is willing to tap into in order to survive. We wanted to leave that up in the air a little bit more and create discussion around that more so than ‘oh look, they treated them like animals back then’ – what did you expect, they were going to act like them? I didn’t really want to tell that story because it’s not as clear-cut as that.

Although you want to leave it open for audiences do you have a set opinion?

Jonathan: Well I don’t think you can – it can’t be that clear-cut because we don’t know who these people actually were. But I do think that the way that the convicts were treated certainly did impact on how events like this happened. I also do think that if you take eight people from today and stick them in the wilderness and say ‘we’re not going to come and get you, you have to find your own way there and there’s no food’ people may eventually actually contemplate the same thing. Is it in our nature to kill in order to survive? I don’t know. But I certainly think it’s an interesting debate.

Do you think films about our past help us see our true human nature more than contemporary events?

Oscar: Definitely; I think you get a sense that if you do look at your past and you’re aware of where you are at present, you can get an idea of where you might be going in the future. I think that you do get a sense of understanding about the possibility of human behaviour and experience for sure.

Jonathan: And it is amazing to look back at stories like that of Alexander Pearce and think ‘well this has been happening for centuries and centuries before that’. We do keep repeating these actions, we do act the same way as our past so it’s interesting to look at our past for that reason, because it has happened many times before and that can change who we are.

Why do you think history seems to repeat itself? Don’t you think we’d learn from our mistakes?

Oscar: I think evolution is pretty slow!

Jonathan: (laughs) Yeah!

Oscar: You just think: we’re not that different from the people who existed ten thousand years ago. It’s one of those things; I find violence very difficult to cope with and I’ve got huge issues with it, but at the same time I find it vaguely strange that we would blanket our feelings with it in particular ways where we have ‘no you can’t do it, you shouldn’t do it, it’s wrong’, which is more of a reaction to what it is. Yeah I have huge issues with it, but I don’t think that that’s a helpful, or the only answer we could come up with feeling the things as we are or using extreme violence. I think again, we’re not that different from people ten thousand years ago so why would we think that I, or anyone, can suddenly just go and behave as we’re supposed to behave… it’s quite strange.

Well, we wish you both all the best in promoting the film! Thankyou for talking to us!

Jonathan: Thankyou for taking the time and for writing about us!

Oscar: Thanks for that. And it’s probably better that you spoke to us later after we’d warmed up (in other interviews) and weren’t talking through just one cup of coffee!

–

Van Diemen’s Land opens in Australia on September 24th

Follow the author Katina Vangopoulos on Twitter.

Follow the author Katina Vangopoulos on Twitter.