The history of a national cinema often reflects the history of the country itself. Right now we can argue that Italy’s (general) media is almost monopolised through former Italian PM Silvio Berlusconi’s Finnivest empire, but cinema as a separate entity has passed through powers such as Hollywood within the last century to gain status as an important identifying medium. La Stanza Del Figlio (The Son’s Room) was made after the social comedy emergence of the 1980s – and although not a comedy stands as a prime example of Nanni Moretti’s work. Bringing commentary through satire to the mainstream, Moretti (among other directors) used the realities of life within his filming technique to express social consciousness within Italy.

The period of comedy began within the ‘50s as a strong antidote to the preceding neo-realist period, appealing to the newly-educated audiences; but by the 1990s this had faded (as cinema interest did in general) because of a mass increase in TV subscriptions and audiences. Moretti was never one to follow trends – as more dramatic fare was becoming widely favoured his comedy Caro Diario (Dear Diary) won him Best Director at Cannes in 1994. The turn to mainstream drama wasn’t necessarily of his choice – changing attitudes of TV audiences through Berlusconi was a major inevitable influence. Moretti’s own foray into politics after The Son’s Room, through party Il Goritondo (The Merry-go-round), opposed Berlusconi and the bureaucratic nature of his ruling. However, film has primarily been his most effective way of activism as he records his own histories as a reflection of his country.

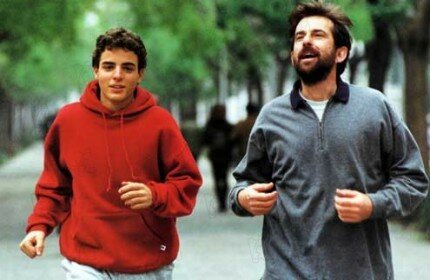

Moretti’s satire has never left him as he refuses to shy away from contemporary issues or critics, while his creative involvement is imperative to his work. As director/writer/producer/star of The Son’s Room, the story of Giovanni and his family reflects how they deal with grief after the death of son Andrea. Focusing on the father and his work as a psychotherapist drives the theme of personal cognition even further as we see Giovanni become disillusioned with his job and life. Moretti uses a mock-autobiographical persona within many of his films, using his own line of thought to create Giovanni’s relationship with his society. Social observations as simple as running and facing the camera are a key motif in the film as he struggles to confront his loss, while the diversity of his patients reflects the different paths available in society. It’s here that contrasts in dealing with death show – Giovanni’s choice to run from his work after Andrea’s death ignites unexpected reactions from his patients, contrary to the humdrum of their usual sessions. His imagination runs rife through the course of the film as we get to know a man who would do anything to change the past, Moretti using flashbacks and fluid camera movements to express where his life has been and where it is going.

By placing himself as the protagonist – the film’s messenger – Moretti seeks personal renewal. Also seen recently in Quiet Chaos, another film dealing with loss and grief in the family, The Son’s Room is an example of Italy’s emotional state; the country’s own social consciousness. Moretti’s use of music is important in recognising the pop culture of mainstream Italy, the prevalence of English songs suggesting the emergence of commercialism and tying into Berlusconi’s media and sudden political influence. It’s necessary to note that the film was affected by politics regardless of Moretti’s views – public television station RAI, run by leading political parties, contributed to the production. The censorship within the Berlusconi era no doubt would have influenced some of Moretti’s choices as a filmmaker and is a reflection of the monopoly Italy’s media finds itself in.

The Son’s Room was well received in Italy, returning the best box office receipts for Moretti yet. As a Palme d’Or winner, it stands high as a film that draws on the open emotion of Italian nature to comment on society. Moretti’s interest in film technique provides him with options in expressing his concern for his country, with satire usually safe in providing laughs but also displays the irony of Italian people and power. This film indeed provides satire but dramatically informs us that we can’t escape grief; we must move forward to become ourselves again – but whether that relates to Italy and its controlled media is for the people to decide.

Follow the author Katina Vangopoulos on Twitter.

Follow the author Katina Vangopoulos on Twitter.

![Quiet Chaos [Caos Calmo] (Review) Quiet Chaos [Caos Calmo] (Review)](/wp-content/uploads/quiet-chaos-father-daughter1-150x150.jpg)

![The Three Musketeers [2011] (Review)](/wp-content/uploads/the-three-musketeers-21-e1319607229980-150x150.jpg)