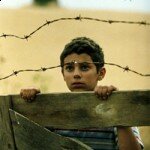

The eyes of a child provide a unique perspective to a situation, usually surrounding views of innocence and make-believe. Italy once saw youth portrayed as the perfect ally to the Fascist regime, the key to vitality and modernity. That theme continued into the Leaden Years of the 70s as students protested against corruption of the Mafia – the innocent caught up in a guilty world. This is the core idea of Io non ho paura (I’m Not Scared), Gabriele Salvatores’ 2003 film that reflects much of his work – social commentary with the use of escapism. He raises questions of innocence and family secrets which reflect Italy’s reserved traditionalism while dealing with part of their ugly past.

Set in 1978, I’m Not Scared is based in Basilicata, a poor isolated region in Italy’s south used in the Fascist period to send opponents into exile. The protagonist is Michele, a 10-year-old boy who thrives on adventures with his friends and whose views are influenced by the fairytales he reads at night. We see his story in chapters as he discovers Filippo, a young boy kidnapped for ransom – Salvatores weaving a major issue of 1970s Italy into the tale. The rural location also reflects the lack of education that surrounds the country’s poor areas, but this doesn’t affect Michele as he starts to slowly understand the power of a secret.

|

As Michele stumbles upon Filippo, Salvatores raises ideas of familism and melodrama. He presents the story through the eyes of the child (literally via a shorter eye level and wider shots representing broad focus) as it acts upon his world. It’s also worth remembering that children also see things in a more exaggerated way, affecting their school, friend and family relationships. Salvatores asks the questions about Michele’s ability to deal with less trivial and more adult information through the secrets his family keep as well as his own, and the experience makes him grow throughout the film. However, the innocence is never truly lost as the fairytales he reads put events into perspective and his decisions remain that of a boy his age. Children are always taught about right and wrong, which is essentially a black-and-white perspective – but as we understand, more often than not there are multiple shades of grey.

Stop all this talk about monsters. . . . monsters don’t exist. It’s men you should be afraid of, not monsters.

Novelist/screenwriter Niccola Ammaniti created Michele’s town and its people as sinister under the surface, but shows father Pino as having split personalities. He pressures Michele to do the right thing for his family, setting ideas of right and wrong but failing to extend the ideals past that point. Arguments between the two often show the difference between the child’s moral honour and the adult’s ethical honour, with neither necessarily right or wrong but presenting the idea that fear comes from what’s unfamiliar (what we struggle to convey, to ourselves and others). Italian families living in extreme poverty, particularly in the South, often show signs of backwardness because there’s a lack of community action – the idea of familism (spending more time with family than neighbours) spread in this part of the country over the 70s period and remains in some remote communities today.

|

The North/South divide prevalent in the previous Retrospective films is seen here with the inclusion of family friend Sergio. Played by Salvatores regular Diego Abatantuono, the man from Milan represents the Northerner attitude as seen by the Southerners – obnoxious, uncaring for others and domineering. Michele immediately registers his displeasure towards Sergio – as a kid would, living what they act and revealing emotion. The neo-realist look on Michele here is that he’s a knowing victim, and as directors Vittorio DeSica and Roberto Rossellini often portrayed, definitely not a delinquent or corrupt. It’s what surrounds him that presents a dark metaphor for Italy – familism as a result of weak national identity and the uncertainty of how to deal with secrets and their implications. Michele learns his fate and accepts it; even at a young age he understands that the hero does fall, contrary to what’s depicted in his fairytales.

I’m Not Scared is more subtle in its criticism of Italy, not because of the younger protagonist but because the little details adding up to an entertaining story that does hint at Italy’s problems. A child’s eyes are indeed different, but in no way does that discount the problems a country faces. The story of Michele serves to prove that morality can go a long way and that sometimes Italy may need to see its problems in plain black and white in order to fix them.

Follow the author Katina Vangopoulos on Twitter.

Follow the author Katina Vangopoulos on Twitter.

![The Three Musketeers [2011] (Review)](/wp-content/uploads/the-three-musketeers-21-e1319607229980-150x150.jpg)