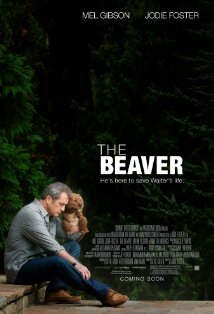

Lately it seems as though Mel Gibson, the actor, has been replaced by Mel Gibson, the publicly drunken and anti-Semitic nutjob. One would suspect that’s why Jodie Foster’s The Beaver has been collect dust on the shelf for the last year, waiting until all the hullaballoo has died down and audiences start to rediscover Mel Gibson, the actor, once more.

The irony here, however, is that it’s because of Gibson’s personal woes that his starring role in The Beaver is so desperate, poignant and strangely comical. Gibson embodies Walter Black, a man on the verge of losing himself completely to the abyss of depression. Interestingly, Walter’s vegetative existence is not a result of his life lacking anything – he is, or was, a well-to-do toy exec with a healthy family — but rather an inexplicable, seemingly inescapable numbness that one day drew the curtains and refused to reopen them. His broken-hearted wife Meridith (Foster) wants nothing more than to see her once-loving husband return, but in a bid to prevent his self-implosion from scarring their two sons, teenager Porter (Anton Yelchin) and youngster Henry (Riley Thomas Stewart), she holds back her tears long enough to kick Walter out of the house.

A slapstick attempt at suicide awakens Walter to a new desire to ‘fix’ himself, placing him at the mercy of a self-prescribed hand puppet that prefers to be addressed simply as The Beaver. Ventriloquising with a deep cockney accent, Walter begins to live his life exclusively through The Beaver, personifying the puppet with the kind of gusto and gall he presumably possessed before his depression left him a crumpled sack in a fancy suit. Naturally, the Black family and those around them — audience included — search for answers: Is this a joke? Has Walter completely lost his mind?

Guided by the natural eye of Jodie Foster, The Beaver sidesteps any idiotic characteristics that would be expected from a movie about a guy who talks to a puppet for ninety minutes. Instead, Foster delivers a carefully directed, quietly comedic story that perfectly integrates the puppet into its execution, making a seamless transition between the characters of Walter and The Beaver. Without a fault to pinpoint, traditional shot-reverse-shot dialogue is filmed to integrate the actions and heavily opinionated reactions of The Beaver. An intriguing matriarch emerges from within Meredith when the Black’s need to rely on their husband and father the most.

As with most films that deal with characters at their breaking points, there is no turning back for Walter. Comparisons with Craig Gillespe’s Lars and The Real Girl and Sam Mendes’ heavily decorated American Beauty will be inevitable, and this film possesses all the qualities of a golden trophy contender for both Foster and Gibson – if, of course, his troubled public profile doesn’t hold the film back.

For a man with such severe mental illness, there is no single moment of awakening — a testament to the careful craftsmanship of screenwriter Kyle Killen in in his debut feature. When Walter and the Beaver finally go head to head, his family, his career and his life are on the line, as they always were. But it’s only now that Walter realises just how much they’re worth fighting for.

Verdict:

A return to form for Mel Gibson and an example of Jodie Foster’s great eye for directing, The Beaver makes for a creative portrayal of mental illness, and of family life around those who live in the dark, reaching a fine balance of drama and comedy.

![jodie-foster-anton-yelchin-the-beaver-movie-image-2[1] jodie foster anton yelchin the beaver movie image 21 e1312528112144 The Beaver (Review)](/wp-content/uploads/jodie-foster-anton-yelchin-the-beaver-movie-image-21-e1312528112144.jpg)