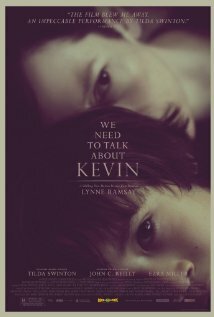

One of the year’s most difficult to watch films is also one of its finest. Adapted from the award winning novel by Lionel Shriver, We Need To Talk About Kevin is a stunning psychological drama and thriller that will set crawling the skin of anyone who watches it… and it will do so without a depicting a single moment of violence. With mesmerizing control over her craft, Scottish director Lynne Ramsay (Ratcatcher, Morvern Cellar) has crafted a rare movie where the story and the direction are in near perfect harmony. Every shot, edit and moment of soundscaping in this film contributes to a single overwhelming sensation. And that sensation is nausea.

The Kevin of the film’s title is played by three young actors: Rocky Duer as an infant, Jasper Newell as a six year old, and Ezra Miller (City Island) as a teenager. All three boys wear the same cruel smirk of a sadistic child who delights in manipulation and cruelty, and whose fascinations grow increasingly violent as he grows older. The film picks up a few years after Kevin commits a mass killing at his high school, and follows Kevin’s mother Eva – played by the always fantastic Tilda Swinton (Burn After Reading) – as she tries to rebuild her life in spite of the persecution from the community her son tore apart. But a majority of the narrative takes place in flashbacks, as Ramsay offers us glimpses into Eva’s marriage and Kevin’s upbringing, urging us to try and pinpoint the moment when things first started to go wrong.

Although it is based on a book, We Need To Talk About Kevin stands very much a part as a work of cinematic craftsmanship. Ramsay’s control over the film is remarkable, and her direction evokes a harrowing atmosphere that envelops the audience, hypnotizing them even as they wish to turn away. She tends to favour extreme close-ups, particularly of character’ eyes and mouths, lending to intense feelings of claustrophobia and disgust. Like Eva, we feel stifled. We feel trapped. Tactile reds flood the colour palette, as substances as innocuous as paint, jam and pureed tomatoes all take on the sticky consistency of blood. Even the smallest touches of production design – a portrait of a clown in a paediatrician’s office, or a motivational poster on a gymnasium door – contribute to a sense of revolting irony, and an increasing awareness of the violent shadow lurking just behind the idealised American veneer.

Feelings of disconcertion are heightened by the films’ sound design, certainly amongst the most impressive of the year. Ramsay frequently overlays the audio from scene to scene, further muddling the timelines and distressing the senses. Screams give way to cheers as garden sprinklers tick rhythmically away, even as the unconventional score of wavering violins, plunking mandolins and eerie whistles by Radiohead front-man Jonny Greenwood strains on behind it all. Hideously jaunty pop music accompanies scenes of desperation and despair, with Buddy Holly’s “Everyday” used to particularly chilling effect. The combined visual and aural cacophony sends shivers across your skin, like razorblades scraping across glass.

Unlike Psycho or Rosemary’s Baby, We Need To Talk About Kevin offers no clear explanation as to why the eponymous character behaves the way he does. It’s clear from the way that she stares in distaste at her pregnant figure in the mirror that Eva was never meant for motherhood, anymore than her husband Franklin (John C. Reilly, Step Brothers), oblivious to his son’s true nature, was meant to be a father. A few key moments of editing suggest unsettling psychological similarities between Eva and Kevin, and yet Kevin’s sister, born six years later, turned out just fine. Ultimately, We Need To Talk About Kevin provides no resolution to the nature versus nurture debate, except to suggest that the best thing to do might be to not have children at all.

With no exploration of Kevin’s psychology, We Need To Talk About Kevin is essentially revealed as an exploitation film; a movie that presents lurid, taboo subject matter for its audience’s enjoyment. Only Kevin doesn’t aim at enjoyment. Kevin aims at exactly the opposite. Which may leave you wondering why anyone would want to watch the film. The answer lies in the appreciation of Ramsay’s craft, which is truly, traumatically magnificent.

Follow the author Tom Clift on Twitter.

Follow the author Tom Clift on Twitter.