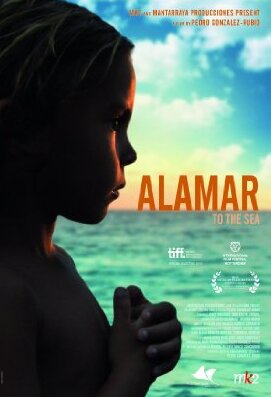

Mexico’s coast houses one of the world’s most beautiful atoll reefs and the country is trying to gain a World Heritage site honour for Banco Chinchorro, which is displayed to beautiful use in Alamar. This may be the reason for making the landscape such a large part of this film, as well as director Pedro Gonzalez-Rubio’s love for documentaries. He’s created a hybrid of style (and colour) for his latest feature, showing a carefree way of life as a father and son revisit their Mayan origins.

Jorge and Roberta have separated since the birth of their son, and Italian Roberta is about to return to Rome having had enough of Mexico – taking young Natan with her. But Jorge is desperate to show his son where he comes from, so before Natan leaves Jorge takes him to visit the patriarch (grandfather Nestor) and show him their traditional way of life. Natan reacts badly to his first boat ride and takes a while to settle in… but even when he does not a lot happens. We see the three generations fish, take it to sellers and then eat some for themselves. Natan finds solace in his Nintendo DS while Jorge and Nestor dive for crabs, and when he is interested it’s not necessarily about the culture or how they live. He just wants to be close with his dad. And that is what Alamar ends up striving to be about. The father-son relationship is a heavy focus, but it’s all a bit drab. Jorge isn’t the liveliest of fathers, although it’s clear Natan adores him even when he’s scolded at. While their relationship is meant to warm our hearts (Natan does over anyone else), it ends up not amounting to a whole lot. This could be put down to lack of plot or feel of genuine affection for these characters but either way it’s a problem that doesn’t fix itself.

Gonzalez-Rubio’s choice to create a hybrid doesn’t work – even with the cast playing themselves and a good premise, the idea to script only some of the film ends up creating a series of disconnected sequences. This includes no subtitling in the opening sequence; a distracting beginning for non-Spanish speakers. The only solace is the entrance of a cattle egret bird nicknamed Blanquita; but while a nice touch in a scene involving Jorge and Natan it’s not enough to pull you out of a stupor. The most notable thing is the cinematography (Gonzalez-Rubio’s quadruple whammy also includes screenplay and producer) – the stunning backdrop of the Caribbean makes for beautiful colour, and makes the 35mm shots look as clear as from a HD. But looking pretty doesn’t cut it – shots often linger on the characters for a fraction too long and you quickly lose interest. You don’t know what to make of jumbled scenes when it’s Hollywood-style one minute and someone’s talking into the camera the next. Alamar doesn’t know what it wants, and it doesn’t give you much to think about.

Verdict:

Alamar takes us to the sea but it’s only good for the scenery.

Alamar screens as part of the Hola Mexico Film Festival across Australia.

Follow the author Katina Vangopoulos on Twitter.

Follow the author Katina Vangopoulos on Twitter.

![Alamar [To The Sea] (Review)](/wp-content/uploads/alamar2-e1289440568268-700x312.jpg)

![Alamar [To The Sea] (Review) ALAMAR1 Alamar [To The Sea] (Review)](/wp-content/uploads/ALAMAR1.jpg)

![A Useful Life [La vida util] (BAFF Review) A Useful Life [La vida util] (BAFF Review)](/wp-content/uploads/hi_usefulnotmain1-e1299120919579-150x150.jpg)

![180 Degrees [180 Moires] (Review) 180 Degrees [180 Moires] (Review)](/wp-content/uploads/180m-150x150.jpg)

![Leap Year [Ano Bisiesto] (Review) Leap Year [Ano Bisiesto] (Review)](/wp-content/uploads/27253.thumb2601-150x150.jpg)

![Loose Cannons [Mine Vaganti] (Review) Loose Cannons [Mine Vaganti] (Review)](/wp-content/uploads/67_1824mayin_11-150x150.jpg)