“There are no secrets that time does not reveal”, recites Australian director Robert Connolly (The Bank, Three Dollars), echoing the words of 16th century French dramatist Jean Racine. Connolly’s latest film, the factual political thriller Balibo, greatly attests to Racine’s wisdom. It brings to the fore a damning piece of Australasian history that, for the last 34 years, the Australian and Indonesian government have desperately attempted to bury.

But Balibo isn’t merely a didactic recount of the five Australian journalists - labeled the ‘Balibo Five’ – who travelled to East Timor in 1975 to report on the impending Indonesian invasion, only to never return. As a film, it’s easily one of the most haunting, thrilling and engaging cinematic experience of the year, which has just as much to say about today’s political landscape as it does yesteryear’s.

With Balibo opening nationally on August 13th, I was given the opportunity to talk to director Robert Connolly and actor Damon Gameau (Thunderstruck, The Tracker), who plays Greg Shackleton, the Channel Seven news reporter who was one of the Balibo Five. During our interview, we discussed the contemporary relevance of the film, what lengths they went to keep the film as factual as possible, how the victims’ families and the Indonesian government have responded to the film and why the film’s star, Anthony LaPaglia, initially only had a cameo in the early drafts.

Spoiler warning: In the same way that some might consider “Adolf Hitler committed suicide” a spoiler, this interview openly discusses the outcome of the events at Balibo. If you’re not at all familiar with the events, maybe consider seeing the film first, and then returning to read this interview.

—

CUT PRINT REVIEW: You’ve said yourself that this is a story that “demands to be told”. Why do you think it took 34 years for that to happen?

ROBERT CONNOLLY: Well someone said to me Gallipoli took seventy years to get made, Breaker Morant took ninety after the Boer war and that we’re actually quite quick off the mark! (laughs) But it is a weird thing for Australia though that – you know, America was making films about Vietnam within two years of the war finishing. So it’s a really good question to ask and I don’t really know, though I think the political sensitivity of this story really made it difficult for filmmakers to make it.

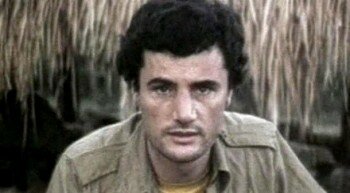

|

Balibo director Robert Connolly |

So was there any pressure from the government to prevent this story from being told?

CONNOLLY: Hard to know because you can never really find any evidence of that. But other people have tried to tell it. There’s part of me that also thinks that maybe some of the other films just focused on the Balibo five, and that falls into the genre of ‘white man saving the third world film’. We found a different way into the story, and maybe that helped this to get made when the others didn’t. I know there are half a dozen filmmakers who have tried to get this made actually.

What kind of relevance do you think the film has today?

CONNOLLY: We were just at the international press conference in Helsinki, a month ago, and they monitor the number of journalists that have been killed each year. Last year there was something like seventy journalists killed, already this year there’s been thirty. They’re really worried, in an ongoing way, that journalists are being killed because they’re journalists. The Balibo Five story is a real turning point because, prior to that in the Vietnam War, journalists had been caught in the crossfire and the action, but hadn’t been targeted as journalists. Whereas the Balibo Five is a tragic turning point because they were killed because they were journalists. So I think its relevant today where we continue to have journalists exposed to the risks.

But it’s complicated because when America attacks Baghdad it takes out Al Jazeera on day one.

DAMON GAMEAU: That’s right, it’s their first target.

CONNOLLY: So yeah, you got to say we’re complicit in that, you know? So I think it’s very relevant in that regard.

Damon, as someone who wasn’t around to see the events of 1975, why was it that you wanted to be a part of retelling this story?

GAMEAU: Someone was telling me that in one of the marches in Iran a couple of weeks ago that the Government officials were told not to target the demonstrators, but to shoot the people with the mobile phones that were filming the actual rally. So the snipers were told to actually target those guys instead of the protesters. So you realise just how pertinent it is, still.

You realise that, increasingly we are living in a world, in a society, where what we know and what we are told by governments is vastly different to what is actually going on. I think even more so today, the press and the lack of free press, that this story seemed so relevant today. As an actor, it’s not very often you get to play someone who you perceive as quite heroic. Someone that died doing what they actually loved doing. You don’t get to play noble figures, you know, the scripts you invariably get sent talk about breaking up with your girlfriend or having a fight.

So to play someone that actually existed, and actually died doing something they were passionate about, is fantastic.

Was there a lot of pressure put on you portraying someone like Greg, given he has a family looking to preserve his memory?

GAMEAU: They were so accommodating, I never felt any pressure. I guess the only pressure was kind of self inflicted, what with the responsibility and weight in what we were doing. For me, my dealings were mainly with Shirley [Shackleton], Greg’s wife. For me personally, she was so supportive, to the point of saying;

“Greg did have some difficulties with people, he did rub them the wrong way, and feel free show that. He was very ambitious and a bit prickly. I want you to show that.”

As an actor, that’s so liberating! You realise you don’t have to sentimentalise anything. You don’t have to make this guy a really friendly guy that everyone loves, you can actually make him a bit more three dimensional. As a result, people relate more and it’s harder to watch when they actually die because they’re real people and not this kind of mythologised version of them.

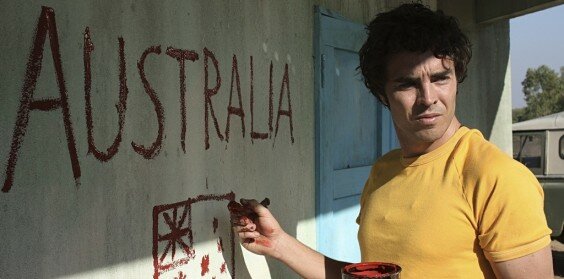

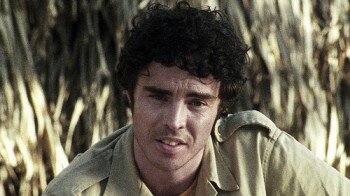

|

Damon Gameau as reporter Greg Shackleton in Balibo |

What was it like coming to an end of your journey as Greg and filming his final moments…

GAMEAU: It’s very hard to describe. It’s like, you spend two months researching someone, spending time with their family, and then you actually witness their death. You live through their death. That’s a very hard thing to explain to anyone, because you’ve immersed yourself in this person – his diary and his family – and suddenly you watch your life go into him and it’s… quite harrowing. It’s a big responsibility that you take on and that you have to be quite savvy with that because you’re toying with big, powerful emotions.

I read a news article from 2004 stating that some of the families of the Balibo victims were “horrified” you were making a film based on Jill Jolliffe’s book ‘Cover Up’. Given how many had campaigned for years to actually shed some light on the issue, why were they so reluctant to see this finally occur?

CONNOLLY: I can’t imagine they were horrified; I think that Shirley [Shackleton] was the only one that was a bit worried. They love the film now, and that’s what matters to me. To have them all on stage at the Melbourne Film Festival was great.

So you think it was misquoted in the media then?

CONNOLLY: Well I think it may have been Shirley? But I don’t know.

GAMEAU: I think they were all naturally apprehensive, because it’s a story they’ve had for 34 years and for someone to come along and – suddenly you meet a guy who’s playing your husband. You know? Imagine the trepidation of getting it right, because they do want the story to be told accurately.

Yeah, I think film is one of those touchy mediums where it’s either done right or taken completely the wrong way…

GAMEAU: Oh yeah, this could have been a catastrophe.

CONNOLLY: I was terrified! When I showed it to Shirley Shackleton I was horrified. I had to put on a screening for all the families as soon as we finished it, we promised that. Because you do feel a responsibility dealing with real people. It was a great relief that they liked it, because releasing the film now, if they hadn’t, it would have been a catastrophe.

What if one of the family members didn’t like it, would you have gone back and changed the final edit?

CONNOLLY: No I wouldn’t have changed it. Having said that, we did listen to their views in the development of it. Between 2004 and when we made it, we spent a lot of time with them. [Damon] got to know Shirley quite well. I met with all the families to hear their views. But it’s like a lot of things; when you’re trying to get to the bottom of the truth, it’s really hard – you can’t be too influenced by them.

GAMEAU: Also after 35 years, people’s versions of truth are – everyone’s got a story or they’ve got an anecdote about something. There are so many things that come in to it.

|

A 2005 photo of Shirley Shackleton, Greg’s wife. |

It must not have been easy to bring up those memories 35 years later…

GAMEAU: Oh, I can’t even imagine that and how confronting that is for them. But the families to us – for the five boys – they were so supportive. To the point where I remember the night before we did the execution scene, Shirley said to me earlier ‘ring me anytime’. I rang her that night and asked her about how she would have thought Greg would have reacted. And to actually give me an answer to that…what a gift that is. You know?

CONNOLLY: Yeah, it’s pretty incredible.

So what other lengths did you go to in order to keep the film as factual as possible?

CONNOLLY: The coroner’s findings in 2007 were amazingly helpful. She interviewed dozens of people she bought out from Timor. I sat in on a lot of them and read her findings, so the murders of the men were based on that. That’s the factual background on that, which was great. We also had a consulting historian, Dr. Clinton Fernandes, and we also had people who were actually there. When we were in Balibo, we had Lt. Colonel Sabika – the man in the film with the red bandanna, who is now in his sixties and a Lieutenant in the army – he came to show what happened on the day. He even came out to MIFF [Melbourne International Film Festival], wasn’t that great!

GAMEAU: So many parallels like that, of people we met, that were actually there at the time. Even in that massacre scene at the end, a lot of those extras were direct relatives of people that had lost their lives on the actual day. So you can imagine the commitment they had. Like, you have ten takes of something, and these girls will be crying after ten takes, because they wanted the story told.

CONNOLLY: It does weigh heavily, that responsibility as a filmmaker to try and get it right. And you are fictionalising it; like you are interpreting the truth.

At the end of the day though, you are trying to engage and entertain the audience as well as educate them…

CONNOLLY: That’s right. I mean, there’s a buddy story and it’s a political thriller. I don’t want it be a lecture, you know? Navigating all of that with this film has been incredibly complicated over many years. It’s amazing how it’s come together. (laughs)

GAMEAU: When you look at it like that, the amount of things that could have gone wrong – this could have been such a catastrophe. (laughs)

CONNOLLY: Yeah, it’s like someone said; to make something work, you have to walk that fine line between utter failure and success. If you just make something average, well, it’s easy to do that.

So what was the biggest part of the film that you had to fictionalise?

CONNOLLY: I think the biggest thing was hypothesising about the dialogue between [Jose Ramos-]Horta and [Roger] East, and their dynamic. I mean, Horta told me some stuff. But I was inspired by the film The Queen, which hypothesised the dialogue between the Queen and Princess Diana. It’s really interesting because Horta since said to me; “you know, there’s stuff in there that you’ve made up, but it’s all possible that it could have happened.”

It reminded me of something Raimond Gaita said when we made Romulus, My Father, which I produced. He said; “there’s not one event in the film which is as it happened, but there is not anything that’s untrue in the entire film.” (laughs)

It’s an interesting question; what is truth? I mean, we were trying to get to the truth of it, but it’s not a documentary. We don’t have transcripts of what they said. So you know, the pool fight and the journey and all that – there’s a lot of stuff we added.

GAMEAU: It’s similar with our stuff, too. We had the actual footage that Channel 7 and 9 provided, like Greg’s piece-to-camera. But what was fun in the process was recreating what actually happened before that piece. So you get that lovely piece in the hut with the kids where they’re listing to the stories. So we actually got to put in place what would have happened that lead up to Greg’s piece. That was great to expand on the story.

|

A comparison between Greg Shackleton’s original piece to camera (top) |

I read that that you initially planned to use Greg’s original piece-to-camera and not actually recreate it like you eventually did. What made you change your mind?

CONNOLLY: Well his performance was going really well up there [East Timor], so Damon and I had a chat and he decided to have a go at it. We were in this remote place, and there was this hut, and we just tried it and it was magnificent. And I think, emotionally, it would have pulled the audience out to see the real footage…

GAMEAU: It would have been strange, in retrospect, it would have been odd.

CONNOLLY: I think the other thing was we were so effectively reproducing that footage with the old lenses. We took up lenses from the seventies, and older cameras.

Wow, so that ‘old film look’ wasn’t just an effect added later during editing?

CONNOLLY: No, that was all achieved using the old lenses.

GAMEAU: Yeah, it’s why it’s got that old seventies, grainy, documentary look.

And all those pieces you see, where my character spoke to the camera, we had them all. I had them on my iPod video. So we’d get to exactly the same location for that shot and then we’d match the shot. So we’d get the extras to sit in there, notice that ‘oh that kid had his shirt off’ or ‘those soldiers stood over there’. Even the director of photography would zoom in at the same time. So we absolutely recreated the look. It just added to the authenticity of it.

I found it interesting that the film is centred on the little known sixth Journalist Roger East. Why did you choose to tell the story from his perspective?

CONNOLLY: Well, the early drafts were just about the Balibo five, so it changed as we were developing it. And you can imagine, as we were researching this, you discover this other journalist in the story that you don’t know anything about. So what happens is you develop his story, and you’re going ‘wow, here’s this amazing 52 year old’ and then you discover that Horta actually came along and encourage him to go up there.

|

Anthony LaPaglia in Balibo. |

Given East isn’t as well known as the other five, did it help to tell the story from his perspective as it would, in a sense, be original to the audience?

CONNOLLY: Yeah, it’s a surprise. That’s what I’m finding; people watch it, and they think the Balibo Five are dead, and they can’t bare it, and they think Roger East is going to go back…

GAMEAU: they think the film’s going to wind down.

CONNOLLY: I remember with the script – it was a big thing [screenwriter] David Williamson and I discussed – was this idea that after they were dead, that’s the highest point of the film. Like, ‘five men get murdered, how can you possibly have a third act after that?’ But somehow or another, there’s the tragedy of the hundred Timorese being killed on that warf – so it becomes about the Timorese and not just Roger East and the Balibo Five.

GAMEAU: That’s where it gains its integrity, because it isn’t just about these five white guys. Yes, that’s integral to the story, but the absolute catastrophe is the fact that 183,000 people died as well. A lot of Australian’s aren’t even aware of that.

Spoiler warning: the hidden content below might contain a substantial spoiler. We suggest you reveal the passage only if you’ve seen the film.

[spoiler]

To be honest, I really didn’t anticipate Roger East’s death. I guess it comes down to the fact that with films you subconsciously think that the main character, or at least someone, has to survive in the end.

GAMEAU: Yeah, I think that’s why at the Melbourne opening on Friday, when he actually got killed, this woman was absolutely distraught. Like, convulsing and wailing out loud in the cinema, because you just don’t expect that to happen.[/spoiler]

When Anthony LaPaglia proposed the idea of Balibo to you, did he know he was going to be playing a key character in the film?

CONNOLLY: No, when he put it forward it was all about the Balibo Five, and he obviously couldn’t play any of them. I think he was more interested in the story. Then in time, the Roger East character came along. It was really good fortune for him that the character of Roger East came to the fore, because early on he was just playing a cameo as some journalist.

GAMEAU: Really?!

CONNOLLY: Yeah, those early drafts… one day I’ll give you one of those early drafts and you just won’t believe it.

GAMEAU: So was he still on the adventure as the journalist?

CONNOLLY: No, no. That was all added. It was just about the Balibo five.

GAMEAU: Wow, yeah ok. I’d love to read that draft one day.

CONNOLLY: Even Horta was barely in it. No Timorese characters or anything. I think the script went on the same journey Greg Shackleton and East went on. You begin worried about the Balibo Five, but in time you care for that nation. The script went on exactly the same journey; it went from just being about the Australian based guys to ultimately the entire nation of East Timor. That’s why we added the Juliana story framing it.

It’s interesting that parallel. The families say the same thing; that initially it was all about their own personal tragedy, but in time they started to care for East Timor.

What kind of research did LaPaglia do for East’s character?

CONNOLLY: He talked to a lot of Roger East’s friends. He met up with a bunch of them in Darwin, like those he used to go fishing with.

GAMEAU: They sent him emails too. When we were on set, they sent him this email saying that he was also a chronic smoker and drinker, and he was like “oh, brilliant, I’ll put that in!” (laughs)

CONNOLLY: (Laughs) But he did do a lot of research. We met up with Roger’s best mate Ken White and he lives down in Werribee, near Melbourne. He had all of Roger’s original dispatches, and that was very helpful.

GAMEAU: Yeah, the research material we all had access to was astonishing. Like I had Greg’s poems, his diary and the letters he had written. It’s just amazing.

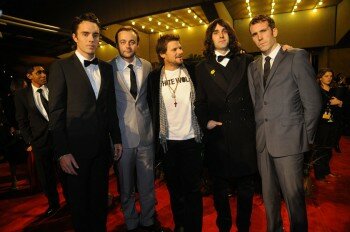

|

The cast of Balibo on the red carpet at the |

You’re saying you had the actual diary from Gerg’s time in East Timor?

GAMEAU: Yeah, like one of the only things that survived, was his diary! It had a day by day account of who he’d met, his feelings, he’d write little poems and one-liners. There are a lot of scary parallels.

You recently had the film’s premiere at the Melbourne International Film Festival and I read that you, Damon, walked the red carpet holding Shirley Shackleton’s hand. What was that like?

CONNOLLY: Well Shirley goes, “Meet My Husband!” on the red carpet! (laughs) She said to me, “I’m so happy that I was married to Damon Gameau when I was a young woman!” (laughs)

GAMEAU: She said to my girlfriend on the night, “get your hands off my husband!” (laughs)

But yeah, it was a big night for the families, an amazing night for them. They finally get recognition and an understanding of what they’ve been through.

What’s your opinion on director Ken Loach’s decision to withdraw his film Looking For Eric from the Melbourne Film Festival, after he found out the Israeli government was a minor sponsor?

CONNOLLY: I feel that film festivals shouldn’t be censored on political grounds. I said to Richard [Moore], the director of the festival, “this shows just how relevant the film festival is.” Whenever people say ‘cinema is going’, here’s this event in Australia’s cultural landscape – this film festival – that’s got all these governments and individuals attacking it. I mean, it shows that they’ve got great relevance.

There’s also been a lot of news about how the Chinese government hacked the Festival’s website, trying to boycott it for screening the documentary about exiled Uighur Congress leader Rebiya Kadeer.

CONNOLLY: Oh that’s amazing isn’t it. You know, Richard told me that the website received 80,000 hits that day on their website, so when that stopped working, it was the phone calls. Some of their staff were really upset because they’d pick up the phone and there’d be this Chinese person just abusing them. So one phone would ring, and when they hung up, the next one in the room would ring. Then they even started seeing people lurking around. Intimidation, mate. Intimidation.

But for Richard, he said; ‘should I resign at the end of the year?’ You know, because it’s a high point for him. As a festival director, what more do you want! You want to be relevant.

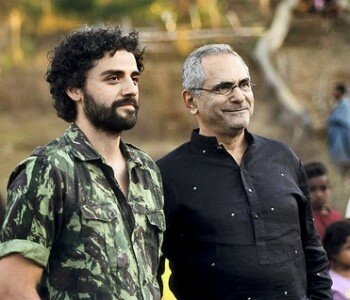

|

Actor Oscar Isacc standing alongside East Timor president |

So what do you want to come out of this film once it’s released?

CONNOLLY: Well firstly, I want it to correct a historic wrong and put on the record what actually happened and inform people about that. I mean, I do also want a lot of people to go and see it. That’s why we’ve made a lot of commercial choices with the thriller format. And the families really want justice; the coroner’s findings, which are currently with the federal police, have recommended a few people that should be tried. I know that the families share a view that maybe the film will help pressure the government to honour the findings of the coroner. But that should be announced this year; it could be, bang, right in the middle of this release.

Are you looking for any kind of response from the Indonesian government?

CONNOLLY: Yeah, well we’re doing a Bahasa subtitled version for Indonesia. I think Indonesia today is a very different place. I think that both Indonesia and Australia should be able to look at that time through 34 years of history. Unfortunately, they’re not really. But there’s an optimist in me that says a younger generation of Indonesians will. You know, Indonesian actors that are your age, who were extras and everything, they’re like “yeah, our country did that. That’s part of our history. It’s good a film’s being made.” It’s more so the entrenched government that continue to, you know…

GAMEAU: It was a militia run government back then and they also killed 5,000 of their own people. So even the younger people today in Indonesia see that as a horrible time in their own history. Since they’re democratising so fast, they’re kind of willing to share and open this up to the world.

CONNOLLY: You should Google the Jakarta post article on the film where it quotes the Indonesian government.

I did read that actually; didn’t it say something like they ‘consider it a work of fiction’?

CONNOLLY: Yeah, that it’s “firmly embedded in the imagination of the director.” (laughs)

GAMEAU: That’s a hell of an imagination you’ve got! (laughs)

CONNOLLY: They say that “they died in crossfire”. Well, here’s a 180 page coronial report that shows that they were murdered. I mean, you know, how many years can they deny it.

GAMEAU: They have to say that though, don’t they…

CONNOLLY: There’s a famous quote from Jean Racine from the 16th century; “there are no secrets that time does not reveal”. I think politicians should be made very aware of that.

But I want it to correct the wrong of 34 years of concealing it. We’re also taking it to Canberra to screen it for all the politicians. You know, it’s definitely got a political agenda. You’re saying that the government concealed this for all these years.

GAMEAU: They’re going to have to make a statement…

CONNOLLY: They’ll have to say something. The government’s bizarrely learned nothing from history; by concealing the truth and lying to the public – it’s a film about journalists too so you’re also lying to journalists. I mean, for God’s sake…

But it draws so much more interest into the story.

Given the overwhelming critical and audience response to the film already, it surprises me that the film isn’t receiving a wide release in Australia. Why is that?

CONNOLLY: It’s a platform where Paramount is co-venturing it. Like a typical platform, it’s got a showcase release initially. So on August 13th, it’s got a showcase release on a limited number of screens. Then it goes regionally on August the 27th. Then on September 10, Paramount is taking it out wide across the country.

If we hit the ground running and I opened it in two weeks, and I opened it across Australia – you know, Public Enemies is out. In Melbourne, it’s on the side of trams. Like they’ve painted entire trams with it and you look at that and go, “my God, the marketing budget…”

So what we depend on is that showcase. But unlike a platform release, where you’re hoping it does well, we’ve just committed and said “no it is going to do well.” I remember in America when Baz Luhrmann released Moulin Rouge, he opened on like four prints for two weeks. I saw it in New York and there were people queuing for miles. So I’m hoping that with this showcase, that kind of thing will happen.

|

A scene from Balibo. |

How about internationally; what are your expectations releasing it there?

CONNOLLY: We’ll be launching the film overseas sometime this year and hoping that we get good traction there.

People say the title is an issue, but then I say look at Gallipoli. That’s even like Balibo as a title – ‘Bal-ee-bo’ we get, or ‘Bill-bao’.

GAMEAU: Remember that film Babel a few years ago?

CONNOLLY: Yeah, America called it Bab-el. (laughs)

GAMEAU: I love the story about how they initially were going to call this film ‘The Balibo Five’. But all the Americans were like, “but we haven’t seen Balibo Four!” (laughs)

One last question for you Robert; as a member on the board for Screen Australia, I needn’t tell you just how amazing this year has been for Australian films. Why do you think the local film industry is so strong at the moment?

CONNOLLY: I think that the mistake the film industry makes is when it tries to work out what films it thinks audiences want, and then cynically makes a whole heap of them. Which is why we once had eight or nine comedies in a row. But my thing is diversity. Diversity is the trick. So if people know, that out there in the market place there’s a range of big films like Baz’s Australia, our film, a little film like Samson and Delilah, which is personal and powerful, a comedy like My Year Without Sex. Then you’ve got Last Ride, Disgrace, and even Mary and Max, an animation. So I think diversity is what makes the audience feel like there’s momentum in the industry. There’s no more or less films, it’s just that they’re so diverse now that people can’t quite believe it. So that’s my big thing with Screen Australia; trying to work out how to maintain that diversity.

I often heard people say “oh, they’re all high art.” Then along comes Wolf Creek. I remember that year, when Wolf Creek came out, everyone was talking about all the other films and then this little horror film gets made and is released in America on 2,000 screens. That’s why I think you have to spread the different types of films across the year. So one week there’s a film with John Malkovich set in South Africa [Disgrace], and then the next week you’ve got a film like Cedar Boys set in Western Sydney.

—

Balibo opens nationally on August 13th, 2009.

So what do you want to come out of this film once it’s released?

Follow the author Anders Wotzke on Twitter.

Follow the author Anders Wotzke on Twitter.

![shirley-web[1] shirley web1 255x350 Robert Connolly and Damon Gameau talk Balibo](/wp-content/uploads/shirley-web1-255x350.jpg)

![3669977829_035b68567f[1] 3669977829 035b68567f1 290x240 custom Robert Connolly and Damon Gameau talk Balibo](/wp-content/uploads/3669977829_035b68567f1-290x240-custom.jpg)