For too long, horror movies has been typified by senseless levels of gore, irritating jump scares and bimbo characters with more botox than brains. But change is in the air. Thanks to the success of films such as The Blair Witch Project, [REC] and Paranormal Activity, the handy-cam style of filmmaking has effectively helped revive the genre into something worth screaming about.

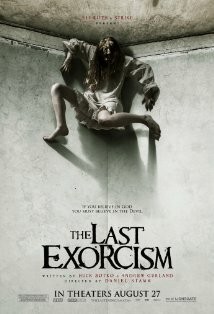

For proof, see Daniel Stamm’s low-budget chiller The Last Exorcism. This excellent piece of genre filmmaking employs the faux documentary approach with such proficiency, it actually manages to elicit supreme scares out of one of the oldest tricks in the book: creepy long-haired girls in white gowns. Truly the Devil’s playthings.

“If you believe in God”, begins the charismatic Reverend Cotton Marcus (Patrick Fabain), “you have to believe in the Devil.”

But Reverend Cotton does not believe in God. He was raised on the word of the bible without ever being given the chance to question his faith, yet continues to preach using his gift of the gab to put dinner on the table for his young family. While his ethics are certainly questionable, the documentary film we’re essentially witnessing – complete with shaky, unfocused camerawork – is Cotton’s way of clearing his conscience. His plan is to conduct one last exorcism in order to prove they’re really nothing more than a con created by means of smoke and mirrors, allowing faceless cameraman Daniel (Adam Grimes) and producer/director Iris (Iris Bahr) to tag along and capture it all on camera.

Cotton answers a plea for help from country farmer Louis Sweetzer (Louis Herthum), a religious nut who believes his overly sweet and meek teenage daughter Nell is possessed by a demon. While Nell’s troubled brother Caleb isn’t pleased about the intervention, Cotton goes ahead with the exorcism, or more accurately, magic show. To set the scene, Cotton cunningly uses hidden iPod speakers to make demonic sounds and rigs up fishing wire to rattle the paintings. The exorcism has the desired placebo effect and Cotton gets paid handsomely. All is well. That is, until Nell inexplicably shows up at Cotton’s motel room in the middle of the night covered in blood…

Regardless of being fabricated, what’s impressive about The Last Exorcism is just how well it works as a documentary about religious fanaticism and faux exorcisms. It’s so compelling, in fact, it’s almost disappointing when the film transitions into horror. On top of the authenticating mockumentary style, Stamm’s film is such a fresh take on the overused exorcism plot because it doesn’t automatically jump to the conclusion that paranormal forces are at play; there’s always more than one rational explanation to everything that occurs. This also means Cotton and the documentarians are just as dubious as we are when things do get a little bit spooky, questioning whether there is more of an earthly evil going on behind closed doors at the Sweetzer’s farmhouse. Has Nell’s father or brother abused her? Perhaps Nell is just a nutcase in need of psychiatric help? Or maybe a demon really has possessed her? All of these are possibilities, and all of them are equally terrifying. It’s a sign of terrific screenwriting.

It’s a shame genre films are seldom recognised by award committees because Patrick Fabian (of TV’s Big Love fame) is beyond exceptional as Reverend Cotton. With a disarming sense of humour, Fabian’s performance is magnetic, selling every piece of dialogue as his own – I can’t remember the last time I truly believed (and liked!) a horror movie character as much as I do here. Cotton loves the sound of his own voice, so the moment he is lost for words, it is monumental. Young Ashley Bell (TV’s United States of Tara) is just as impressive at playing the all-important dichotomy of Nell, switching between sweet and bubbly to demonic and disturbed like there’s nothing to it. As Nell’s apprehensive brother, newcomer Caleb Landry Jones might just be the film’s biggest revelation. In an early scene, he absolutely nails the role of passive aggressor, proving that a slight smile and uneasy tone of voice is eons scarier than anything more classically confronting.

As a slow-burning character-driven horror, The Last Exorcism doesn’t put a foot wrong until the finale, where it unfortunately goes belly up. Although it is effectively frightening, it feels rushed and regrettably negates all the intricately handled themes raised earlier. But to get caught up in what goes wrong in the last five minutes is to unjustly discredit everything brilliant about the 80-odd minutes beforehand. The Last Exorcism is a rare reminder that the genre label “horror” derives from the word horrifying, not horrible.

Follow the author Anders Wotzke on Twitter.

Follow the author Anders Wotzke on Twitter.

![2010_the_last_exorcism_004[1] 2010 the last exorcism 0041 e1290744151467 600x337 The Last Exorcism (Review)](/wp-content/uploads/2010_the_last_exorcism_0041-e1290744151467-600x337.jpg)