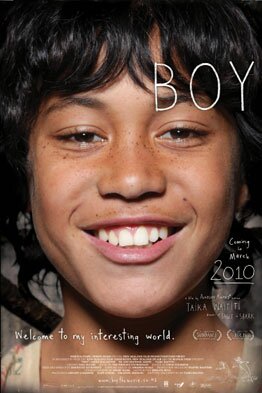

Before it won the Audience Award at both the Melbourne and Sydney film festivals, Taika Waititi’s Boy became the highest grossing New Zealand film of all time. For good reason, too; this captivating coming-of-age drama tackles sobering themes with comedic sensibility, masterfully balancing big laughs and big heart without compromising either.

The year is 1984 and Michael Jackson’s Thriller is inescapable even the remote coastal community of Waihau Bay, New Zealand. One of MJ’s biggest fans is 11-year-old Alamein Jr. (James Rolleston) — or ‘Boy’ as he prefers to be known — who lives with his Grandma after the death of his mother and absence of his jailed father, Alamein Snr. (Taika Waititi). When Gran leaves for a week, it’s up to Boy to look after the farm and look after his withdrawn 6-year-old brother Rocky (Te Aho Aho Eketone-Whitu).

One night while Gran is away, three gruff-looking men wearing bikie jackets roll up to the house in a black muscle car. “I’m your dad” says one of the men, prompting Boy to invite them in for a cup of tea.

Far from the heroic Shogun warrior he had envisioned, Boy’s father is really a daft man-child who spends his days smoking pot and avoiding all responsibilities, only returning home to recover a bag full of money buried in the paddock. Whatever his reasons, Boy is just glad to be able to spend some quality time with his dad, viewing him through the same starry eyes as the King of Pop.

This is only Waititi’s second feature film to date (after 2007’s Eagle vs. Shark), yet the writer, director and actor already exhibits the kind of across-the-board talent of a master filmmaker. Although the story is fictionalised, Waititi has drawn from his own upbringing in rural New Zealand during the 1980s, credibly capturing a time, place and atmosphere that is uniquely Kiwi in character. If The Castle is Australia’s national treasure, Boy might very well be New Zealand’s.

With no previous acting experience, 11-year-old Rolleston is exceptional in the titular role, countering his childlike optimism with a level of maturity far beyond his age. Opposite Rolleston, Waititi plays the kind of deadbeat character audiences are usually predisposed to loathe, but the strength of his restrained screenplay and on-screen charisma is that we’re just as susceptible to Alamein’s charms as his son. As a result, we become so emotionally invested in both these characters that we go against our better judgement and hope, wishfully, that things work out between them.

Boy is often quite tragic in its depiction of unfit parenting, abandonment and various addictions, yet the film’s deft sense of humour – reminiscent of TV’s excellent Flight of the Conchords, episodes of which Waititi has directed – keeps you smiling even when you’re on the verge of tears.

Not since 2008′s Oscar winner Slumdog Millionaire has pleasure and pain come together so beautifully.

Follow the author Anders Wotzke on Twitter.

Follow the author Anders Wotzke on Twitter.

![Boy [2010] (Review)](/wp-content/uploads/boy-e1283155516568-700x416.jpg)