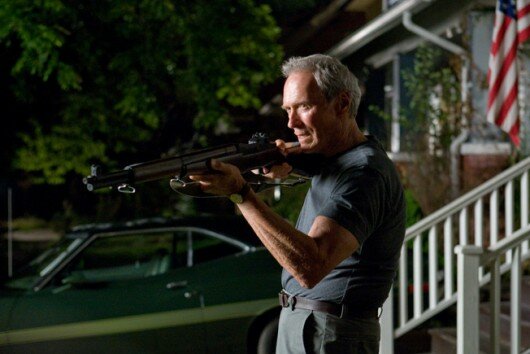

Dirty Harry has got nothing on Korean War veteran Walt Kowalski. When 78 year old Clint Eastwood menacingly snarls “Get off my lawn” to a fierce Hmong gang, he may as well be infamously sneering “make my day” as top-cop Harry Callagan.

However, Eastwood’s latest film Gran Torino is unlikely to make your day, nor ruin it. Juggling the roles of director and lead actor, something he’s mastered countless times in the past, Eastwood only manages to find mild success with both. Maybe it’s because he has too much on his plate for someone about to venture into their 80′s; off helping Angelina Jolie find her son in the upcoming crime/drama Changeling. Or maybe he was having too much fun directing himself as the disgruntled and bigoted Walt Kowalski that the patchy story and notably sub-par cast in support slipped through unnoticed. Either way, Gran Torino‘s shortcomings mask its successes, making it hard not to think of the film as a minor work from the American icon.

If recently widowed Korean War veteran Walt Kowalski (Clint Eastwood) is not sitting on his porch scornfully eyeing off the latest addition to his immigrant neighbourhood, he’s out in the garage polishing his prized 1972 Ford Gran Torino. When Walt’s withdrawn Vietnamese neighbour Thao (Bee Vang) is pressured into joining a local Hmong gang, his initiation test is to steal the Gran Torino from the seemingly harmless old man. Met with a gun pointed at his head, Thao learns first hand that Walt is anything but harmless, failing his initiation and pitting the gang against his family. In order to make up for his wrongdoing, he asks Walt for forgiveness, who in turn attempts to reform the Hmong teen so he can legitimately make it by in the world.

|

Probably too stubborn to admit to it, but Walt is also reformed by Thao. Beginning the film as a blatant racist, slating his Hmong neighbours as “barbarians”, Walt later on comes to the realisation that he has “more in common with these Gooks than [he does his] own family”. The film is certainly not shy of exploring ethnic prejudice that exists in modern suburbia, using blunt humour as a way to ease the audience into issues with racial gangs, liberalist ideals and general cultural disparities. Yet most of the time it explores such issues too predictably, often glossing over them with a stereotypical eye. For instance, the blatantly simplified racial gangs speak smack-talk like they are out of a video game, not a film bearing an important message. For this reason, Gran Torino is at its best when it is not taking itself too seriously.

Clint Eastwood must have realised this, as his overstated bitterness manages to prevent the film from falling completely into ‘generic drama’ territory. In fact, the film shines when Eastwood’s performance throws subtlety out the door; in a scene where Walt’s family are tactlessly showing him pamphlets for retirement homes, the utter disgust on his face accompanied by a low growl is nothing short of hysterical. Yet as soon as his character is asked to make somewhat of a transformation, the result is quite stiff; his caricatured bitterness doesn’t handle the shift towards compassion all that smoothly, or interestingly. By the time you’ve grown accustomed to his blatant bigoted remarks, and dare I say start enjoying it, the film starts to gear itself for the self-serious ending that doesn’t suit or compliment the humorous first act. Ultimately, it’s not the Oscar worthy performance some have suggested, but Eastwood’s comical portrayal as Walt does manage to hold the film together.

|

Yet anything Eastwood does here would look Oscar worthy in contrast to the film supporting performances. Hard to imagine, but maybe Eastwood’s budget ran dry; whilst Changeling boasts the likes of John Malkovich and Angelina Jolie, Gran Torino boasts nothing more than cringe worthy performances from a supporting cast that might look the part, but certainly don’t act like it. Bee Vang as the troubled Hmong teenager Thao is incapable of bringing any emotional depth to his character beyond what is revealed through his awkwardly delivered dialogue. When the film is a comedy, the one-dimensional performances by the Hmong cast are passable as being complimentary to Walt’s overstated snideness, but as soon as the film takes a serious turn, their inexperience noticeably prevents the film from evoking the emotional response needed to make the films ending stick.

Conclusion:

Gran Torino ends with an odd ballad performed by Eastwood himself, almost as if it’s his Swan Song for starring in his own films. I can’t help but see this as a good thing, as Eastwood stretched himself too thin here; his strong comic performance is undone by a misguided story and poor casting. It’s enjoyable, yet despite desperately trying, it falls short of being anything more.

Follow the author Anders Wotzke on Twitter.

Follow the author Anders Wotzke on Twitter.