Directed by the ever-so-masterful Stanley Kubrick in 1962, Lolita is a surprisingly lacklustre affair with a script that’s neither as daring nor erotic as it so desperately wants to be.

The film follows Humbert Humbert (James Mason), a middle-aged British college professor who movies to America in order to acquire a position as a French literature teacher. Upon crossing the pond, Humbert stumbles upon a small town where he rents a room from Charlotte Haze (Shelley Winters) — an insecure, baffling woman.

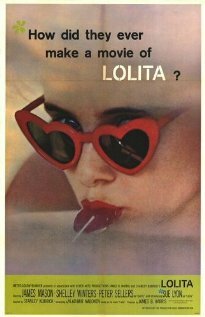

He soon goes onto marrying here for one very peculiar, though simplistic reason: to get closer to her 14-year-old nymphet of a daughter, Dolores “Lolita” Haze (Sue Lyon, now 65). His obsession with her escalates throughout the film’s protracted runtime, cumulating with a desperate plea from Humbert during the final reel: “I want you to love with me and die with me and everything with me.”

While Lolita is certainly an oddity — it satirises deluded sexual obsessions with no sense of wrongdoing — Kubrick is missing an emotional punch. Not one of the characters derived from Vladimir Nabokov’s classic novel of the same name earn our sympathy. It feels as if Kubrick – who adapted the story with Nabokov for the screen – chose not to treat the characters in the story as beings, but rather as objects. And it’s a shame.

In his first collaboration with Kubrick, Peter Sellers delivers a witty and largely improvised performance as Clare Quilty, a hotshot Hollywood writer whose only purpose in the film is to cause havoc for Lolita and Humbert. Yet Quilty is an unforgivably shallow character who shows up from time to time, acts goofy, delivers some snappy lines, and then leaves. No explanation is given, and the story doesn’t progress.

But really, no need to beat around the bush: Lolita simply doesn’t work as a romantic tale because the foundation on which the film is supposed to be built on — the relationship between Humbert and Lolita — isn’t compellingly told. Not for a second do you believe this sophisticated, though obsessive, literature teacher would fall for a teenage girl, nor beg and plead for her as she walks out the door.

Upon its release in 1962, Lolita was considered ground-breaking material due to its scandalous eroticism, even though the censors allowed very little of it to reach the screen. Viewed in 2011, however, the film is tiresome, constrained, and dated. I’m sure many Kubrick aficionados will be quick to disagree, likely arguing that you cannot critique a timeworn film with contemporary eyes. But a true masterpiece, I’d retort, should be timeless. And while many of Kubrick’s films still enthrall today as much as they did way back when, Lolita isn’t one of them.

–

Sam Fragoso is a web-based film journalist who writes at dukeandthemovies.com.

![Lolita [1962] (Review)](/wp-content/uploads/lolita-kubrick-movie-image-011-e1310700478491-700x399.jpg)

![Glengarry Glen Ross [1992] (Retro Review) Glengarry Glen Ross [1992] (Retro Review)](/wp-content/uploads/glengarry_glen_ross-251-e1308035123256-150x150.jpg)

![Rear Window [1954] (Review) Rear Window [1954] (Review)](/wp-content/uploads/rear-window-original1-150x150.jpg)

![Ages of Love [Manuale d'am3re] (Review) Ages of Love [Manuale d'am3re] (Review)](/wp-content/uploads/ages-of-love-movie-image-robert-de-niro-monica-bellucci-03-600x4001-e1322965752440-150x150.jpg)